Disclosure

I imagine that this may be the first Plain Language Science article many readers will read. I need to head this article with a note that will apply to this article and all articles to follow. Plain Language Science exists to inform above all else. It is important to acknowledge here up top that biology is exceptionally complex, literally everything in these articles has some nuance and additional layers of detail. Scientists have been awarded Nobel Prizes uncovering the intricacies of these topics, discoveries that only an entire career of study can reveal. Though some of this minutia could be topics for future articles, many of these details are beyond the scope of this blog. This blog is a great stop to get a big picture and digestible overview on topics that are relevant and interesting to you, but it is not a substitute for an in-depth scientific education!

Ok, disclosure out of the way.

For now, Plain Language Science will be focused on the broad scope of “biology” as a whole, but biology is a diamond of many different facets. Big-focused and small-focused, inside-studied and outside-studied, the specialties span the gamut. Scientists in each area share some common understandings, but also have their own unique and hard won expertise. A zoologist and an evolutionary biologist for instance have many areas of common understanding. As a stem cell scientist I can coax stem cells to beat, but a quick look at my plant shelf tells you that I am no botanist. Pothos are all that remain.

The specific area of focus for this series of articles is molecular biology, small-focused, inside science. This is the land of DNA, CRISPR and “the mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell”. This is the area where I possess existing knowledge, a good place for me to start.

The Cell

Now we can’t dive too deep into anything biological without briefly going over the most important biological entity, the cell. Cells are the foundation of all living organisms, comprising every living part of your body. Even non-living structures, like your hair, nails, and outer layer of skin, are at least partially made up of dead cells. The cells in your body are living, dividing and dying constantly. Some of your cells only live for a day or two, some are with you for your entire lifetime. Your body alone is made up of between 30 and 40 trillion of them. Yep, with a “t”.

I always like analogies when presented with impossibly big numbers like these, but there is no way I am going to do all this math on my own. According to AI, 40 trillion grains of sand is enough to (approximately) fill the Hoover Dam. It is also enough sand to bury the entirety of New York City two feet deep. To conceptualize how small these cells are, if your cells were actually the size of a grain of sand, you would be around 280 feet tall. Your big toe nail would be the size of a doormat. Needless to say, they are impossibly small, and you have a lot of them.

Cells come in all shapes in sizes, mainly because they are tasked with doing so many different things. The beating cells in your heart are very different from the light-detecting cells in your eyes, or the acid-producing cells in your stomach. The unique capabilities of each of these cell types contributes to the crazy cool complexity of life. This complexity is what makes all of this possible.

We will go over cells in more depth in a later article. I only bring them up now to outline that all this action below is happening inside of these cells. They are the ones leveraging the central dogma every day to make biology happen.

Central Dogma of Molecular Biology

As the name implies, the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology is the foundation for everything in molecular biology. When scientists take introductory classes in molecular biology, this is where they all start. The idea of the central dogma is a simple one, broken up into two statements:

- The DNA in your body is constantly being replicated. As your body makes new cells, the DNA in your old cells needs to be replicated, among other things, to fill these new cells.

- The second statement of the dogma is that the transfer of genetic information proceeds from DNA to RNA to proteins.

We will do an overview of DNA replication after we do a deeper dive into DNA and cell division. For now we will stick to the linear portion of the central dogma. Statement 2 states that the information stored in your DNA is transcribed into RNA information, which is then translated into a protein product.

I’m tossing around words like transcription and translation, but what does it all mean?!

Let’s break it down.

DNA – The Instruction Manual

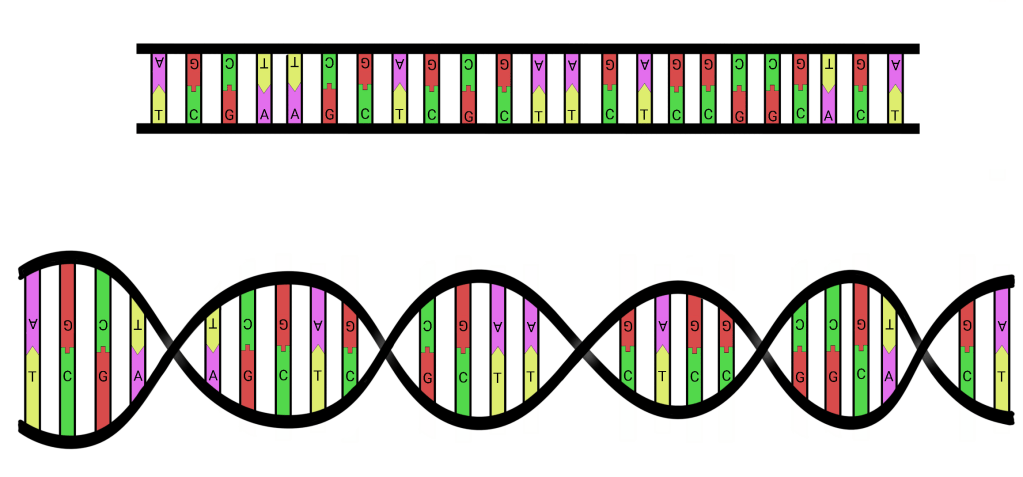

I wish I could remember how I envisioned DNA before I stepped into BIO 100. A double helix of As, Cs, Gs and Ts, called nucleotides, that somehow defines who we are. Your DNA does many different things, but its most important job is to store information. Your DNA, collectively referred to as your genome, holds enough information to not only separate you from a banana, but to separate you from me.

When most people are asked to describe DNA they always mention the twisted ladder, or the spiraling double helix. When you get into this line of thinking it is easy to forget that DNA is actually two chunks of information attached in the middle. DNA is made up of two strands of nucleotides running in opposite directions, and connected in parallel. Each half of the DNA double helix is composed of a strong backbone with nucleotides joining their counterparts on the other strand in the center. The nucleotides meeting in the middle have regular partners. Adenine (A) fits with Thymine (T), Cytosine (C) fits with Guanine (G).

This is the structure of the most vital thing in your body, and the integrity of your genome relies on these two complementary DNA strands coming together to protect the nucleotides within. Your DNA being double stranded is a huge advantage. It protects the goods from getting jostled around too much.

Now, I am sure you have heard of “genes”. These genes are specific portions of your DNA, the assembly instructions needed to make every little thing your body needs to function. Genes only make up around 3% of your entire genome1. Interestingly enough, each one of the cell types in your body has access to the same DNA, and the same catalog of genes. Choosing which genes to use and which not to use plays a huge role in dictating the difference between the cell types in your body. Heart cells don’t need to react to light or make stomach acid. They only use the genes they need, and ignore the genes that make these alternative functions possible for other cells.

In school my brain saw DNA as a library of instruction manuals filled with text. Most of this text is either nonsensical nonsense, extremely complicated or maybe just a language we don’t even understand yet. A very small portion of the text in this library is proper English instructions. Each of these sentences is precise, arranged properly with identifiable punctuation and clear starts and stops to each set of instructions. When a need for a particular item arises, the ding of the front desk bell sends a scribe scurrying off. With a little help the scribe finds the specific body of text in question and jots down (transcribes) an annotation of the passage. That quick note then goes off to a builder to be built (translated) into the final item.

The reason why molecular biologists often describe DNA in a similar way is because the genetic information in your DNA, your genes, are actively sought, located, read and annotated. In your body. Trillions of times per second. These figurative library employees actually exist. We are putting the cart before the horse here, but we can’t go much further without skipping to the end of our dogma story to talk a tiny bit about proteins.

Put simply, if something is happening in your body, a protein has a hand in it. This may be news to you, but your body does a TON of stuff. Proteins are the little machines that make life possible. The genes we went over earlier? The information stored in these genes exists to make these proteins. I won’t spoil it, but one of the most essential roles of DNA is to store the information needed to transcribe many different types of RNA, which are translated in turn into many different types of proteins. This is the essence of our central dogma.

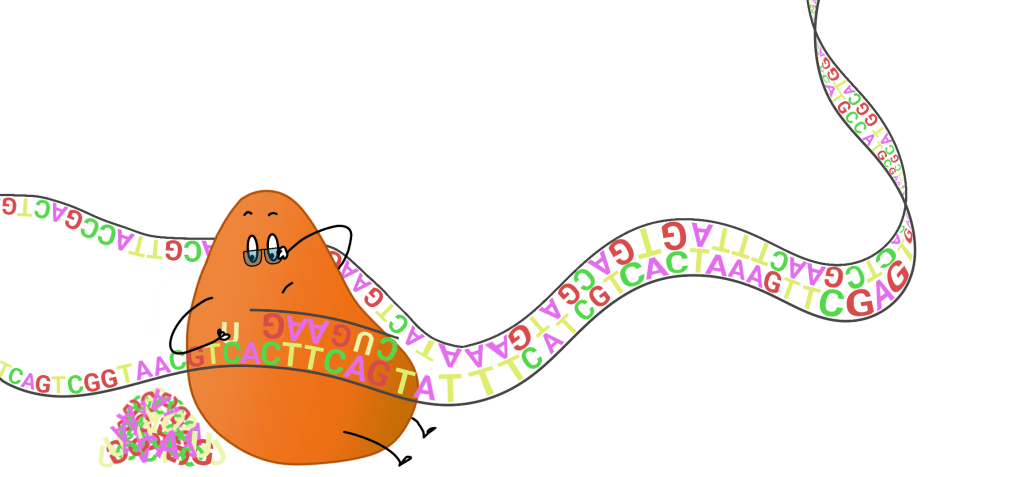

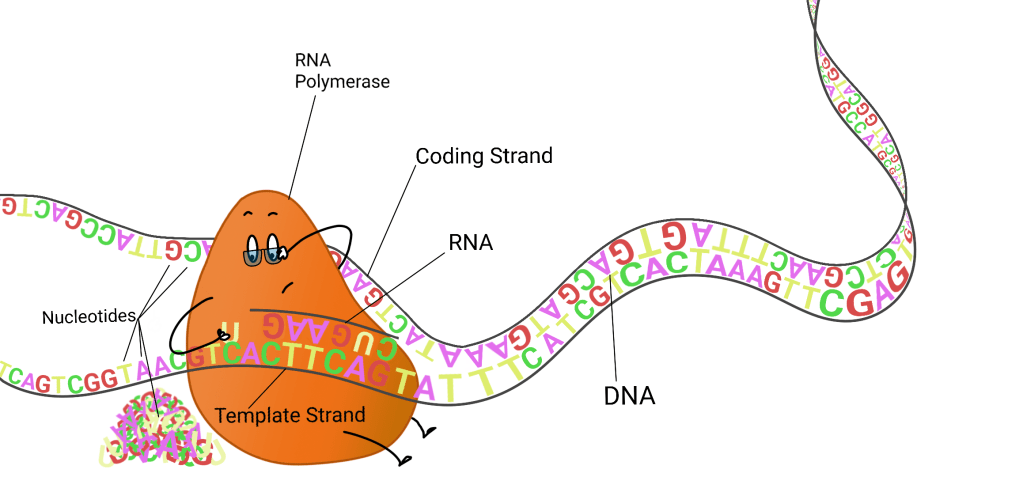

Now, what are these little protein library employees? How are they locating, reading and transcribing these four-lettered DNA tomes? As the disclaimer mentioned above, this article will leave out a few major players in this endeavor to make this toe-dip article as accessible as possible. All the ancillary characters, with cool names like promoters, enhancers, transcription factors, helicase and topoisomerase, will take the back seat for now. One hero of this story that absolutely can’t be omitted is the scribe in our analogy, RNA polymerase.

RNA polymerase

RNA polymerase is one of these proteins. Well, not just a single protein.

Most of the time, a single protein can only do a few different things, they grab something, chop something, support something, signal for something, stretch out, crunch up, etc. In many cases, different proteins with unique expertise need to be joined together to make a multi-functional unit. Proteins will often mighty-morph into large assemblies we call protein complexes. More specifically, RNA polymerase is a macromolecular complex, which is just fancy talk for a complex of both RNAs and proteins, all the requisite parts needed to grab your DNA, scan to find the start of the gene, read the gene and transcribe a complementary RNA strand. RNA polymerase can do all this while zipping through your DNA at around 50 nucleotides per second2.

I can read 50 characters with ease, perhaps faster.

That sentence above is 50 characters long. Maybe you did read that in a second, but could you translate it and write the translation in that second as well?

Your cells can do some cool things.

Transcription

Now you may have caught on to my use of the word “transcribe”. That is what RNA polymerase is doing here, transcribing a gene. Transcription is when a RNA polymerase uses DNA as reference material to write a new message in the RNA polymerase’s own language, RNA.

Remember, DNA is double stranded, with one strand complementary to the other. The target gene will be on one of these two strands. After the DNA is opened, the strand with the target gene is bound by RNA polymerase. This strand is called the template strand, it operates as the template used to transcribe the mRNA. The opposite strand of DNA is called the coding strand. The coding strand complements the template strand, meaning that the coding strand matches the RNA produced by the RNA polymerase. With one major, and admittingly annoying, caveat. The RNA polymerase does not speak fluent DNA. For numerous reasons, RNA polymerase cannot use the Thymine, or T nucleotide. When RNA polymerase comes across an adenine (A) in the template strand, instead of dropping a thymine (T), it drops in a uracil (U). Uracil does not exist in DNA, and it is a bit smaller than thymine but it binds up with adenine just fine. No harm no foul. The exact explanation as to why is out of scope for this article. This could also be the focus of a future article one day!

RNA polymerase does not only make protein-coding RNA, it is capable of transcribing many different types of RNA. Of course, this is entirely dependent on the genes that the RNA was transcribed from. We will only be discussing three types of RNA in this article, messenger RNA (mRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA). mRNA is the type of RNA that will be translated into protein as part of the central dogma, these guys code for proteins. tRNAs on the other hand are not read to make proteins. They have their own job to do. They play a more ancillary but equally important role, and we will go over them in a few paragraphs

RNA – The Quick Note

Have you ever jotted something on your hand? I remember envisioning mRNA in this way during my introductory biology courses. Why? Simply put, it is because it’s a fragile bit of information that needs to be used quickly before it fades to nothing.

Unlike DNA, RNA is single stranded. RNA is missing that second backbone that protects the nucleotide information, making it much more fragile than DNA. However, with all of these exposed nucleotides, RNA will often loop over and bind itself where it can do so, matching nucleotides just as DNA would (except using Us instead of Ts of course). Most times this looping does not fully protect the RNA, but this looping is frequently a feature, not a bug. RNA looping can have major implications down the line (remember tRNA?). When an RNA strand is fresh off the RNA polymerase, it gets shuttled out of the nucleus to the cytoplasm of the cell, where some can degrade as quickly as a few minutes.3

Once this RNA is out in the nucleus, a few different things could happen depending on the identity of the RNA. For now we pick up where we left off with mRNA, which at this moment would be waiting for a partner of its own, a builder, that can translate its precious information into a protein. This builder is known as a ribosome.

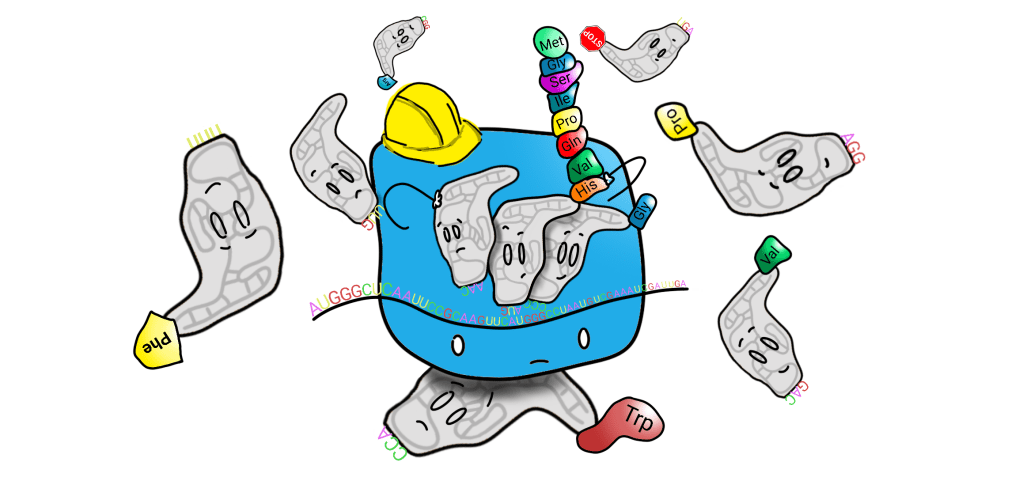

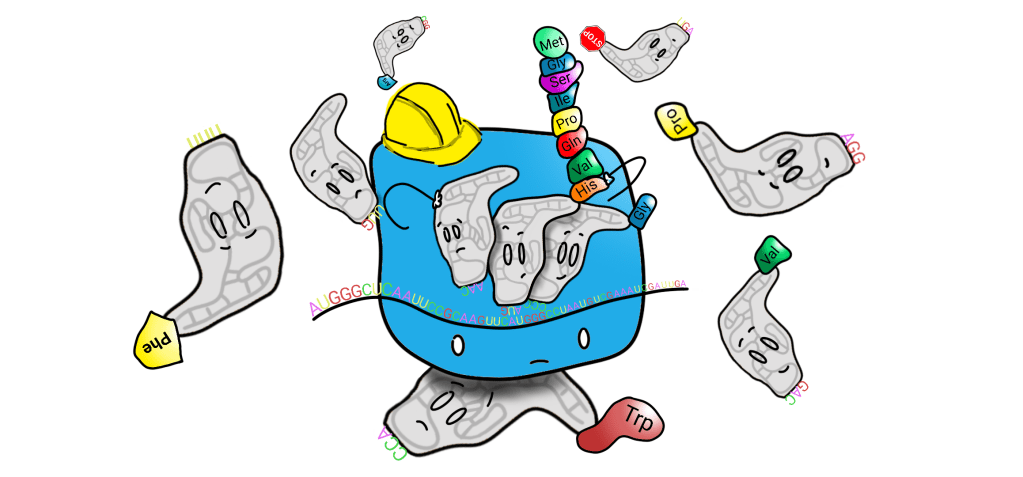

Ribosome

The ribosome is where these blueprints become reality, they are the builders in our above analogy. A ribosome is another macromolecular complex whose job is to bind the mRNA, read the nucleotides, and to build the protein the mRNA codes for. Ribosomes are the beginning of the end of a central dogma.

Translation

So with the mRNA floating out in the cell, it is only a matter of time before a ribosome binds on to it. Once it grabs on, it scans until it finds its start point. Like we parsed down transcription, some of the more detailed aspects of translation will be saved for another article. For now, the key points to internalize are that this wayward mRNA is bound by a ribosome.

This ribosome reads the mRNA instructions, and looks around for some building blocks to start snapping them together to make the protein chain. These building blocks are amino acids, and they are a whole different animal when compared to the nucleotides we have been working with in DNA and RNA.

Amino Acids

The nucleotides that comprise your DNA and RNA are great for carrying information, but they lack a bit of flash. Minimal structural diversity, limited dynamic interplay. A very sub-optimal building block when you are trying to get stuff done. Your ribosomes make a major upgrade in the building material when they switch from nucleotides to amino acids.

Someone very close to me is all about supplements. Fish oil, biotin, multivitamins the size of a AA battery, you name it. You may have someone like this in your life as well. I bring it up because that was my first exposure to amino acids as a kid, through products like Bragg Liquid Aminos. When I was a kid I was told that products like these would give me the extra boost of amino acids I needed to build the proteins I lacked to grow muscle I so desperately wanted. I put that stuff on everything. I can tell you now that this was not an effective strategy.

Unlike the handful of different nucleotides that make up DNA and RNA, proteins have 20 different amino acids to choose from. Unlike nucleotides, amino acids are very structurally divergent, and come in dramatically different compositions that fundamentally affect the way they behave with one another and their environment. It is these types of dynamic traits that make amino acids such a versatile building media. More on this when we take a deeper dive into proteins in a separate article.

Herein lies the problem. Up until now, data has been transferred by simply matching nucleotides to a counterpart, A to U and C to G. Your ribosomes on the other hand need to read this nucleotide input (the mRNA) and produce an amino acid output (the protein). To do this, ribosomes need an intermediary to bridge the gap. A molecule that can help in this translation from nucleotide to amino acid.

tRNA

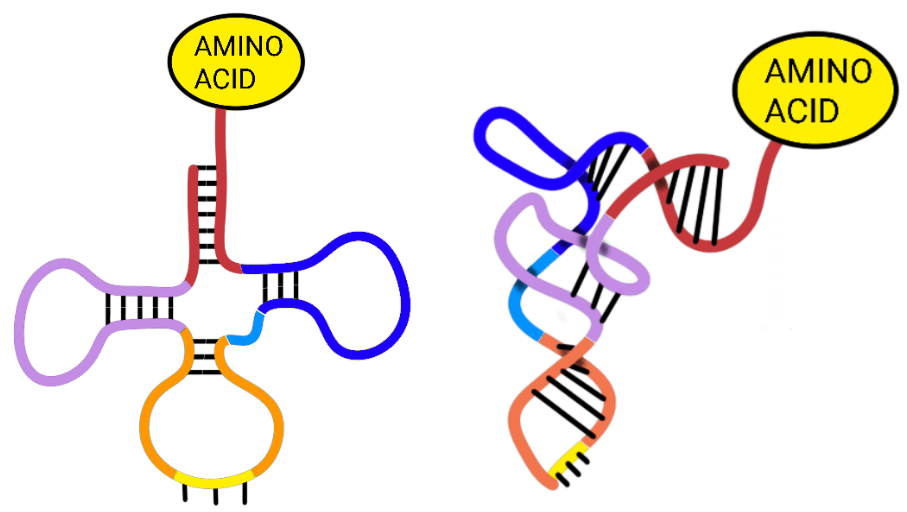

tRNA is this translator. Just like mRNA, these RNAs are coded for by genes in the genome. Instead of being translated into a protein by a ribosome, the mission of the tRNA is to loop up on itself in a very specific shape, called a cloverleaf. It is the tRNAs job to bind the mRNA, and bring along the appropriate amino acid to the ribosome.

As you can see at the bottom of these tRNA molecules, there is a trio of exposed nucleotides. This region of the tRNA is called the anticodon region, and it is exposed to match up and bind the mRNA. This is how mRNA is read, in 3-lettered words called codons.

Each possible three-nucleotide combination of nucleotides is code for a specific amino acid, very much like a decoder ring. The tRNA carries an amino acid that matches their anticodon region, which in turn complements the intended codon on the mRNA. The anticodon region of the tRNA binds the mRNA codon, and the ribosome can then transfer the bound amino acid from the tRNA to the growing string of amino acids.

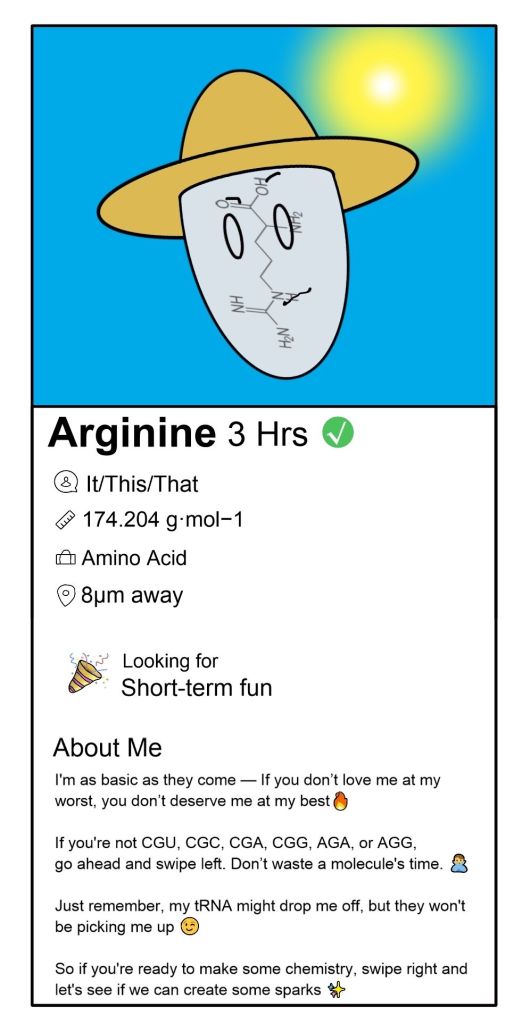

As an example, RNA polymerase would read CCA CGA and put down GGU GCU to match. During translation however, the ribosome would expose the CCA sequence of nucleotides, which would be bound by a tRNA with the GGU anticodon, carrying a proline amino acid. After the mRNA advances through the ribosome byt three nucleotides, the newly-exposed CGA in the mRNA would be bound by a tRNA with the GCU anticodon, which would be carrying arginine. Each amino acid would be removed from it’s tRNA and join the conga line as the protein strand grows.

So when I say that an mRNA codes for the amino acids in a protein, it’s actually a bit more complex than that. mRNA is a string of information that is interpreted by the ribosome as 3-nucleotide codons. These codons match to anticodon sequences that are embedded in tRNAs. These tRNAs carry the matching amino acid that is next in line to join the protein chain. Each portion of the process is an additional step in the cipher. Now you can start to see a reason why this process is called translation.

The ribosome grabs on to the mRNA, and scans down the length. It only starts building the protein after reading AUG, the codon that signals the start of the mRNA sequence. As it exposes the next codon, it waits for a tRNA to match it, and then moves the attached amino acid from the bound tRNA to the growing protein string. Now-empty tRNA’s are ejected and recycled by attaching a new amino acid to replace the old one. The ribosome keeps adding amino acids to the strand until it reaches one of three stop codons, UAA, UAG, or UGA. This a a self destruct sequence. The ribosome falls apart, releasing the protein, and goes on looking for another mRNA to translate. We are left with our final product, our protein.

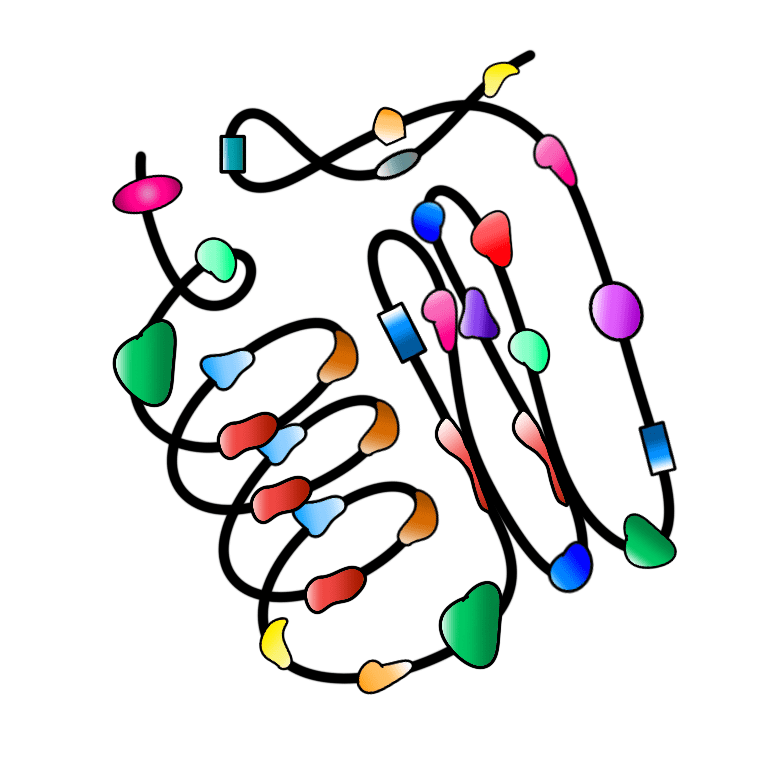

Protein – The Machinery

I always envisioned a protein as a strand of magnetic Mardi Gras beads. Different sizes and shapes, some push, some pull. Some like to be on the outside, some prefer the inside. Every time you let the strand go it snaps into a very specific shape. This propensity to form this same shape every time is due to the properties in the beads.

This is why the unique chemicals properties of the 20 amino acids is so important. The chemical makeup of each amino acid is unique, and has a major impact on how they interact with each other and their environment.

We will dive deeper into this in a protein-focused article, just know that for proteins, shape and composition are everything, these traits are absolutely critical to proper protein function. Once it assumes its final form, your new protein goes off to do its job, whatever that may be.

Ok awesome. Your RNA polymerase reads a gene in your DNA and knits together some RNA. This RNA was moved out of the nucleus where a ribosome found it and gave it a quick once over, using tRNAs to link amino acids together. These amino acids made a big protein that snapped into a specific shape to go run off and do something. That’s all there is to the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology?

In essence, yup. That is it.

It is important to remember that each one of these steps has levels of intricacy that we will tackle when the time comes. For instance, we will need to further explore transcription before we tackle my favorite topic, epigenetics. We will need to dive deeper into proteins and translation before I even attempt to explain the mechanism behind most diseases some of you may be interested in knowing more about. We will have to wade further into DNA to go over heredity and mitosis. I envision this blog as a web, with interlinked branches of related articles in all directions. This article is at the center, it’s all out from here.

You did the thing!

If this article was too long; and you didn’t read it, here is a quick and concise bullet-point summary of what you just read:

TL;DR

- The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology describes the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to proteins.

- DNA serves as the instruction manual, containing genetic information stored as a sequence of nucleotides, A, G, C and T.

- Genes, which make up only around 3% of the genome, are segments of DNA that code for proteins.

- During transcription, DNA is transcribed into RNA by RNA polymerase.

- RNA, single-stranded and more fragile than DNA, carries genetic information out of the nucleus to the cytoplasm using the nucleotides A, G, C and U (instead of T).

- Ribosomes rely on tRNAs to facilitate translation by assembling amino acids into proteins based on mRNA instructions.

- Proteins, made up of 20 different amino acids, are essential for nearly all cellular functions and come in diverse shapes and compositions that are critical for their function.

Sources:

- Makałowski, Wojciech. “The human genome structure and organization.” Acta Biochimica Polonica 48.3 (2001): 587-598.

- Jonkers, I., Lis, J. Getting up to speed with transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16, 167–177 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3953

- Sachs, Alan B. “Messenger RNA degradation in eukaryotes.” Cell 74.3 (1993): 413-421.